@LARGE Ai Weiwei at Alcatraz

17 AprSeven distinct exhibition areas and an incredibly rich artistic programme comprise the @LARGE Ai Weiwei on Alcatraz exhibition. Addressing political prisoners of conscience worldwide (Beijing-based Ai was once imprisoned for eighteen months in his home country of China and is since forbidden to leave), the exhibition questions state versus self-agency in a series of sites for metaphoric exploration and encounters with individual prisoners of conscience in past and current times.

With Wind occupies the New Industries Building where former prisoners of the federal penitentiary were granted the privilege of work. A dragon with its body constructed as a segmented kite and other handmade kites of paper, silk, and bamboo fill the space along its central axis, the dragon’s body curving back and forth from the head at the entrance to the tail at the furthest point back. Some thirty countries “with serious records of restricting their citizens’ human rights and civil liberties” are referenced through renderings of birds and flowers (David Spalding, ed., @LARGE Ai Weiwei on Alcatraz, Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy, San Francisco [2014], p. 55). The craft involved is due to the fabrication by traditional Chinese kite makers from one rural community. The whole is strikingly beautiful. And although the fierce representation of the dragon’s face startles at first glance, the presentation on the whole is ethereal. That a beast of this size could be held within a prison building is incongruous, the artist does not conceive of this as an imprisonment piece, but rather, “represent[ing] not imperial authority, but personal freedom: ‘everybody has this power’.” Individual quotations from prisoners of conscience, including Nelson Mandela and Eric Snowden, adorn the body of this dragon. (See http://www.for-site.org/project/ai-weiwei-alcatraz-with-wind/ [accessed 12/10/2014].)

Adjoining With Wind in the rear of the building is a second installation called Trace. This portrait gallery of 176 prisoners of conscience from around the world, individuals imprisoned for their beliefs or associations, spreads out across the floor in an assemblage of hand-built LEGO bricks. While some portions were assembled in the artist’s studio, more than 80 volunteers in San Francisco spent about three-and-a-half weeks assembling the whole in situ. One docent explained to me that the artist was inspired to use this material watching his son play with LEGOs. Indeed, the viewer comes away with a feeling of an unique transubstantiation where the State has the power to completely assemble or disassemble the individual. Surprisingly, the political heroes presented here include a number of Americans: Chelsea Manning, Eric Snowden, Martin Luther King, Jr. (arrested 30 times in his life) and John Kiriakou. Kiriakou is someone I had never heard of. He is serving a 30-month prison term for “violating” the Intelligence Identities Protection Act by revealing the name of a CIA officer who had been involved in that agency’s program to hold and interrogate detainees and publicly discussing the use of the suffocation technique known as waterboarding. To learn that this country even carries such a law is offensive to me and to know that Kiriakou would be punished for revealing what he has is equally offensive. Kiriakou is a former CIA officer.

One of the seven installations’ most evocative is Stay Tuned, a series of individual audio installations within cells along the A Block of the Alcatraz Cellhouse, a massive structure originally built in 1912 to house military prisoners. Sitting in individual cells, one can listen to, among others: Martin Luther King, Jr.’s April 4, 1967 speech against the Vietnam War (given at The Riverside Church in New York City); Pussy Riot’s Virgin Mary, Put Putin Away (Punk Prayer), two members of the band serving a two-year sentence following a performance of the song on February 21, 2012; and, Chilean singer/songwriter Victor Jara’s (1932-73) Manifesto, from a musician who was arrested, imprisoned, and murdered following the U.S.-backed military coup of September 12, 1973.

There are many other surprises to this exhibition. I urge you to see it before it closes on April 26th. The exhibition was initiated by Cheryl Haines, founding Executive Director of FOR-SITE Foundation. Amnesty International and other human rights organizations worked closely with Ai in developing the programmatic content for the exhibition. Photographs by the author with permission from FOR-SITE Foundation and Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy.

The Unexpected

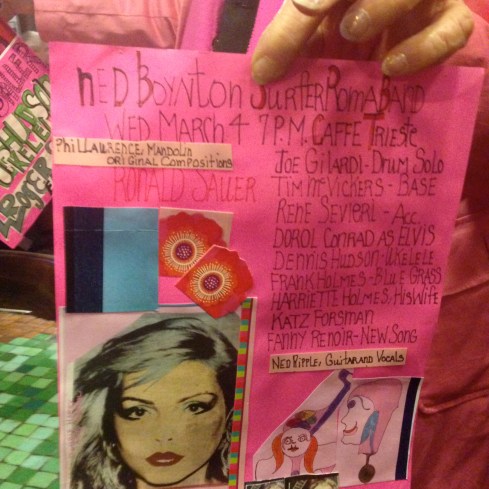

15 AprI am not always happy about the unexpected, but sometimes what I do not anticipate comes to my rescue. Wednesday, March 4th, was a dismal day. I cannot even remember the reasons for my dark mood as the day bore on. But by the time I was ready to relax for the evening I headed over to Cafe Trieste, near my room in North Beach. I enjoy their inexpensive house cabernet sauvignon and that single glass of wine can mellow out any mood I may bring with me to their space. (Their menu prices went up across the board recently, so they no longer serve the cheapest glass in the neighborhood.) They also have a juke box with interesting and varied fare, from vintage rock’n’roll and near contemporary operatic offerings to engaging Italian pop.

Sometimes a group of poets sit together and recite their verse to each other. They are a fixture at the cafe and have probably been sharing their fussy lines since they first found each other. I try to sit away from the sound of their droning tonality, but the cafe this particular evening was given over to a most extraordinary revel.

The first Wednesday evening of the month is host to the Ned Boynton Surfer Roma Band. You can also listen to Boynton play a lilting guitar on the juke box. The Surfa Roma Band is a changing ensemble from month to month. Of the eight members I listened to with great pleasure, there were musicians playing mandolin, accordian, guitar, bass, bongos, congas, and cymbals.

What was utterly charming, though, was the impromptu pairings of dancers, people who knew this event and each other. Their delight was a delicious extravagance. I was warm and beaming by the time the musicians disbanded.

One week later I was expecting one of my clients to fulfill our volunteer garden outing on Alcatraz Island. There is a long history of gardening on the Island. In its earliest European American phase, Alcatraz Island was the site of the West Coast’s first United States military defense point. This was during the Civil War. Military wives established gardens during the second half of the 19th century. I have heard tell of one hundred-year-old rose plants still existing within the gardens. Certainly garden cover can be seen on every side of the Island and is shared by gulls, egrets, geese, ducks, pelicans, and other birds. We discovered a dusky brown newt recently.

My client and I, just getting to know the terrain, join a large group of volunteers, some of whom have devoted their weekly visits to this rocky eden for many years. We both enjoy the activities and setting. Having heard a weather report on rain, though, the day before, he chose not to garden.

Thus I was free to not work on my birthday. Having thought about my sixtieth over the years, I had promised myself to do something big. But, alas, without money, I had to content myself with errands left undone because of a busy work schedule. Then mid-day my friend Nancy called to ask if I would accompany her to see Hugh Masekela in concert that evening; the ticket holder had dropped out. Yes! I had not heard his music in years. This was an extraordinary invitation. The concert was held at University of California, Berkeley Zellerbach Hall, a gorgeous space.

Vusi Mahlasela, a renowned singer/guitarist, shared the stage with Masekela and a band of musicians formed for their 20 Years of Freedom concert tour. Masekela played the trumpet, flugelhorn, various percussive instruments, told stories, sang, and, with Mahlasela, broke into impromptu knee-bending dance.

Perhaps the longest piece, Stimela or Coal Train, was the most riveting, with Masekela speaking the beginning lyrics as a poem: “There is a train that comes from Namibia and Malawi / there is a train that comes from Zamibia and Zimbabwe / There is a train that comes from Angola and Mozambique, / From Lesotho, from Botswana, From Zwaziland, / From all the hinterland of Southern and Central Africa. / This train carries young and old, African men / Who are conscripted to come and work on contract / In the golden mineral mines of Johannesburg / And its surrounding metropolis, sixteen hours or more a day / For almost no pay.” Masekela added sounds of the trains, the workers, the inside of the mines, creating a presence of scene that was palpable. One could feel the very air of movement within those mines. By the end an incredible thing happened: the audience stood up, practically springing from their seats. But this was not a moment when an audience stands to clap. This was a moment when no one knew what had just happened, to their senses, their reasoning, their place in the world.

Masekela is 75 or 76 years old today. He is an exuberant man, as powerful as ten men. Nancy and Hugh showed me the way forward from sixty. Something big had happened, indeed.

As a final note, I recommend a small, unassuming space in North Beach for live music. Melt, at 700 Columbus, just off of Washington Square Park, offers delectable items such as fondue and Welsh rarebit, salads and wine, but also hosts jazz almost nightly. This is one of the few remaining places for jazz in the city, which the owner, a musician himself, acknowledged to me one evening. And perhaps, if you visit, you will have a chance to hear a very talented pianist named Jibril Alvarez, who organizes sessions there.

Feed Your Face, But Do Not Feed the Homeless

17 NovOur Planet Recycling, San Francisco. One bale of tin can weighs about 800 pounds.

Two headlines from November 7th came to my attention: “Tunica hosts Twinkie Eating Contest” and “90-year-old Florida man arrested for second time in a week after feeding the homeless again.” In the case of the first article (Associated Press; accessed online 11/8/2014), one learns that Joey Chestnut returns to “defend” his title in the 2014 World Twinkie-Eating Championship at Bally’s Casino. Noted is his former accomplishment of setting a world-record by downing 121 Twinkies in six minutes (“about one in every three seconds”). Steve Ettlinger cites the Hostess claim that it sells 500 million Twinkies a year (Twinkie, Deconstructed: My Journey to Discover How the Ingredients Found in Processed Foods Are Grown, Mined [Yes, Mined], and Manipulated into What America Eats [New York: Hudson Street Press, 2007]; page 8). With that many Twinkies in the world, we could all become Twinkie-eating contestants. In fact, Chestnut makes it look easy in accessible online videoclips. Be prepared to use your fingers by inserting most of them clumsily in your mouth. Ironically, Chestnut’s sportsmanship is about as exciting to watch as the repetitive arm motion of a Darts World Cup contestant. The elevation of bulimic eating to a sport can only be attributed to our fascination with the grotesque.

I can easily believe Chestnut’s feat as I remember eating Twinkies as an adolescent; it took about three seconds to eat a single Twinkie. That “so appealing” taste that Ettlinger refers to (8) may be true, given the individual nature of taste, but the appealing aspect that I would attribute to the Twinkie and like industrial products is the chemical input and reaction that the human body comes to crave as highly processed food becomes a staple of one’s diet. Do you ever remember singular moments in eating? I remember my friend John Engwerda serving a ginger souffle in his New York home. My god, what an experience! And it will never be repeated. Have you ever eaten the flower from the nasturtium, fresh from a garden? Why do moments like that bring the sensation of taste into pungent experience? But to call a Twinkie appealing as if eating one were an experience of enriching quality is laughable.

I began reading Twinkie, Deconstructed when I was involved in teaching a nutrition class for clients at the workplace. Many individuals from this community consume industrially processed food as the main staple of their diet. It is not uncommon for a client to consume three sodas on a daily basis. As a result, many are vulnerable to obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. (If you are curious about one label ingredient, sugar, measure out one teaspoon per gram to see what amount of sugar you may be consuming.) Ettlinger, who has involved himself with food at its source — gathering mussels in Maine, visiting the Beaujolais district of southeastern France to learn the origin and handling of wine grapes, eating wild raspberries from the yard — took on the project of investigating industrially processed food at its source(s) when his daughter asked what was in ice cream as he read the ingredients on a container. He did not have a way of explaining where polysorbate came from. Finding the iconic Twinkie ideal for investigating the “story of making convenience food, guided by science and commerce” (6), Ettlinger provides a comprehensive narrative of how each of the ingredients on a package list come to be processed, from the source.

You may feel as if you are an Ettlinger child reading his text. Structured as a travelogue, this is a narrative with a lot of explanation that rarely steps back to ponder. For instance, in writing about the vitamin thiamine mononitrate (B1), the author explains that the most common form is synthesized from petrochemicals “derived from that old trusted food source, coal tar”:

“. . . Thiamine chemicals are finished with about fifteen steps that may include, depending upon the company, such appetizing processes as oxidation with corrosive strength hydrogen peroxide and active carbon; reactions with ammonium nitrate, ammonium carbonate, and nitric acid (to form a salt); and washing with alcohol. It is edible at this point . . .” (37)

In this way, the journey is soothing where the information could be potentially jarring. Never mind that you may never have encountered an industrial food processing procedure before; it all works out in the end. On rare cccasion, the author includes brief word on the environmental costs of these industrial processes. For instance, in his chapter on phosphates, we learn that a Western Phosphate Field, within a hundred-mile radius of Soda Springs, Idaho, is the site for the mining of six million tons of phosphate per year. While Ettlinger visits a Monsanto phosphate plant to describe the industrial process of converting phosphate ore into liquid phosphoric acid, eventually to be incorporated into baking powder, the author notes several disturbing facts. Monsanto’s plant is the last of its kind in the United States. This is partly because of the “environmental concerns triggered by its toxic discharge” (157). One such plant, closed in 2001, became a Superfund site because of the level of arsenic and “other pollutants” found in the groundwater (157-8). We also learn that most of the phosphorus produced at this plant is used by Monsanto to produce the herbicide Roundup®. A newer “wet process” elsewhere in the world is superseding this older process.

Still, this examination of industrialized food processing is valuable in showing the awesome scale and science involved. Visiting the trona mine operated by FMC Corporation in the region of Green River, Wyoming, Ettlinger travels sixteen hundred feet below the earth’s surface by elevator to see where this ore is excavated. Trona is converted to soda ash, which then becomes sodium carbonate, then sodium bicarbonate, or, baking soda, one of the three components of baking powder (see pp. 141-52). The author follows it every step of the way. The book includes ample background information on the historical discovery and development of all the industrial food substances explored in the making of the Twinkie ingredient list.

Understanding that the Twinkie is a product of the “rural-industrial complex” with an “international nexus” is fundamental to viewing today’s industrial food processes (256). Given that, the author concludes his book by arguing that we, the consumer, should accept the chemical aspects of this web without reservation. First, history leads us here, such as “mass supply start[ing] to feed mass demand” here in the United States (259). Second, chemicals have always been in our food, as in the case of salt being composed of chlorine (“one of the world’s most lethal chemicals”) and sodium (“one of the most reactive”) (261). These are both false arguments: one must accept the author’s premise because they are presented to support it. Ettlinger’s unabashed enthusiasm overrides any and all concerns. While he states that “there is reason to be vigilant” about industrially processed food (260), we never learn exactly what vigilant concern should entail.

The Twinkie is an answer to putting food on the consumer shelf that is low-cost and readily available with a guaranteed shelf life. And so Ettlinger reminds us: “. . . Before getting on a high horse to decry the excessive pressures of capitalism that force food to be so overwhelmingly engineered, we need to remember this: no farmer would bring his or her crops to market without promise of a reward” (262). Enter Arnold Abbott, the 90-year-old Ft. Lauderdale criminal serving food plates to the homeless. At the time of his second citation, he faced 60 days in jail or a $500 fine (Marc Weinreich, New York Daily News; http:/www.nydailynews.com/. . . ; accessed 11/8/2014). The city ordinance he challenged restricts people from “camping, panhandling, food sharing [italics mine] and engaging in other ‘life sustaining activities’.” Pity food distribution systems that try to function independently from the excessive pressures of capitalism.